Gentrification.

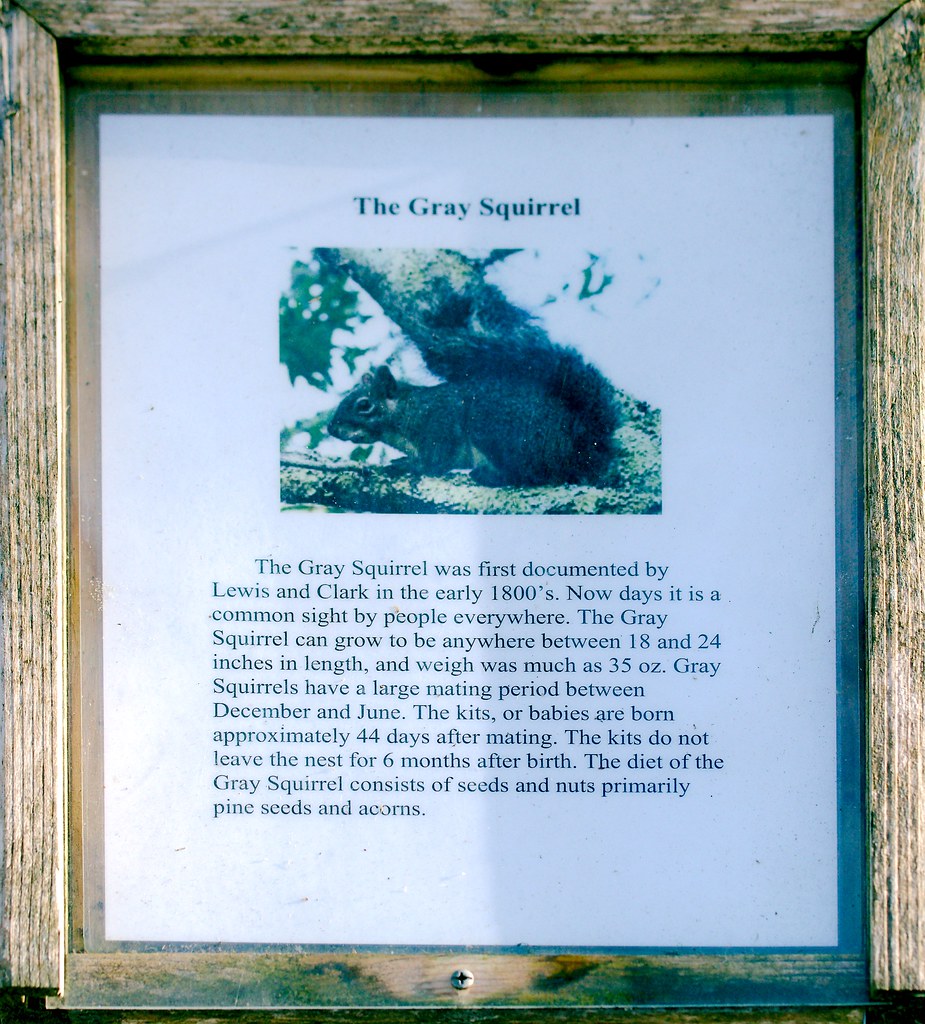

Squirrel Sign

Ice

Bluebird

One weird thing about moving from Illinois to Minnesota is that Spring is less well distributed.

In Illinois, the snow melts away to reveal bright green grass, the buds appear on the trees, and the animals all wake up and come home.

In Minnesota, at the end of Winter, half the snow melts, then the birds arrive (as shown here) and sort of stand around for a while as the plants decide that this is the best they’re gonna get and then turn sorta green. This triggers the rest of the snow to melt, which makes the rest of the plants turn green. Then the mammals come back and enjoy the next two weeks, which we call “Summer”. Then it snows again so we can get the second half of Spring for another week, after which it’s deep Summer for about month, then we get our third week of Spring which transitions directly into Fall, which alternates with Winter every week for about four cycles, after which point it’s Winter for a good five months.

Wide angle infrared

Thinking About Gorillas – Part 2 – Thinking Strategically

Yesterday, I posted my thoughts on the gorilla incident. This is part 2, where in I think about the bigger issues at stake.

- The Cincinnati Zoo opened in 1875 and their gorilla enclosure opened in 1978. Until a few weeks ago, there were zero issues.

- On May 28th, 2016, a young child bypassed several barriers and wound up inside the gorilla enclosure.

- The child was discovered by a relatively young male gorilla, who started moving him around and “presenting”, as gorillas to do gain status.

- The keepers attempted to separate the child from the gorilla, but were unable to do so, though they did get other gorillas out of the way.

- Due to a lack of other options, the zoo decided that the young child’s life was in serious danger and that the only option was to kill the gorilla.

- Because we live in the age of out-of-context smartphone video, this was all recorded so …

- The Internet lost its collective shit and, over a single weekend, millions of people suddenly became self-proclaimed experts in wildlife management and tranquilizers.

I don’t want to talk about any of this. Instead, I want to talk about complexity, and I want to talk about how humans respond both to regular everyday life and to emergencies.

Complexity is called different things in different disciplines. In math and computer science, “complexity” works fine. In politics, it’s called “history”. In history, it’s called “time”. In physics and chemistry, it’s “entropy”. In the biological sciences, it’s “ecology”.

In all these fields, there is a core problem that the further you trace dependencies and inter-relationships, the harder it gets to understand what is happening. As events affect other events and different groups interact, you begin to get emergent behavior. Not only is it hard to figure out what’s going on as the system begins to take on a life of its own, but the more you analyze it, the more you become part of that system, affecting it’s own behavior.

Socially, this is very problematic because we’re all part of these complex systems. Not only can we not clearly see the systems of which we’re part, and how our own behavior affects others, but when it comes to explain our concerns to those in power, the inherent complexity works against mutual understanding. This can be thought of as the fundamental challenge facing our species.

Many species have fundamental problems that they have evolved to meet. Loner species, like tigers and turtles, are challenged by the need to find food without expending too much energy in the process and have evolved weapons and defenses to either increase success in a hunt or decrease the energy cost of foraging. Group species do this through role assignment and communication.

Ants and bees, of course, have considerable specialization and communicate with one another through chemical signals (ants) and dances (bees) to communicate food location for collection and to organize around group defenses.

Birds that live in flocks and mammals that live in herds largely communicate verbally and will coordinate around defense and food availability, migrating as a mass as resources changes.

But primates are more interesting. They coordinate both attack and defense to defend the group, as well as assign individualized roles based on those individuals’ capabilities. Chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas all have group leaders and will all teach skills to others in the group through both active demonstration and verbal communication.

Humans are no different, except that we have a much more complex and powerful language ability. Current theories suggest that the linguistic centers of our brains are used to make sense of the world, so it should be unsurprising that we use language to simplify the complexities we face. We think linguistically. We use words to refer to objects and actions. We use metaphors to communicate complex ideas. We use narrative to describe how the world works and should work. This approach is fast and effective, but can be inaccurate.

If we face a big problem, we first need everyone working on it to agree what the basic words mean – how warm is “warm”? How bad is “bad”?. Then we need to agree to the same metaphorical constructs to simplify the problem – is “climate change” better than “global warming” or “acid rain”? Then, finally, we need to agree on narrative. “Yes, there’s a problem but it is caused by humans or is it natural?” “How will the problem affect me?”

Of course, this process adds complexity to our lives until we reach the point where it is naturally reduced through mutual understanding. Since people dislike complexity, people resist and, as a result, society maintains an ever-present resistance to change. This resistance to change keeps us from making big risks that could harm everyone, but it also makes it hard for us to fix long-running, slow-to-develop problems.

Instead, we need to be forced into action through big dramatic emergencies. Then, when these happen, we quickly run through the complexity simplification process to figure out what to do as a society to prevent such a thing from every happening again.

So let’s take a quick look at why those six common responses to the gorilla incident resonate with so many people.

Bad parents – This thought resonates because we’ve all had some experience of parenting, whether it’s from being a child or having a child/pet/plant of our own. We all tend to consider how we’d react in a situation with more objectivity than we’d have in the situation itself because we’re not in the middle of a fight or flight chemical cascade. This response misses the complexity involved in dealing with brain chemicals, a large crowd of people, an excitable child that may not match the ideal child we have in our minds (or the particular child we’re used to dealing with), with different styles of parenting, and with the different life experiences of parents.

Bad exhibit design – A lot of people like this one because the idea of “how do I safely keep this animal in this space” feels like an easy one to anyone who has a cat or dog. However, this response ignores centuries of people learning from previous exhibit design and studies of animal health and human safety. Most features of an exhibit design are present either because they’ve worked in the past or because they’re an attempt to fix something that no one’s figured out how to fix yet. It also ignores the fact a good exhibit design must be multifunctional. A good exhibit needs to keep the animal captive, be easily cleanable, allow staff to move the animals around during exhibit cleaning and animal medical emergencies, be resistant to the animal’s attempts to destroy it, be resistant to human abuses from the outside, meet all the health needs of the animal (food, water, shade, privacy, physical activity, comfort, etc), *and* be pleasant enough for people to look at it and not think it’s terrible.

This is why the zoos of the past, with cage and concrete, changed into pits in the first place. Now they’re changing again, to hidden barrier systems and mixed-species exhibits.

Bad response by zookeepers – As I noted yesterday, this response misses the complexity of what zookeepers must learn and balance. Each animal is different and, due to staffing shortages, there is often only one keeper that has a really good chance of understanding how an animal will react to a particular situation. Zookeepers have to go through many years of schooling and working very long hours to gain the experience needed to do their jobs. They have to be part biologist, part veterinarian, part janitor, part teacher, and part crisis manager. The job is extremely complex and, to a great extent, entirely unrespected outside of the community.

They do it for love, and to think that anyone would kill what they love because it’s the easy way out is terribly insulting.

Bad response by zoo visitors – When crowds form, you get the interaction of social status with brain chemistry. When something terrible is happening, all your biological systems are effected: heart rate, digestion, breathing, etc. When norepinephrine is released, sugars and fats are converted into energy, which is sent to muscles, which tense up to prepare for fight or flight. This means that higher order functioning is shifted away from the brain and into older, faster, systems such as primate-based hierarchical thinking. So, in a crowd, people care more about protecting themselves and their own family and literally stop thinking clearly. When everyone is making individual decisions along those lines, the crowd as a whole becomes resistant to change as anyone trying to get them to disperse could be a threat.

While the crowd is becoming resistant to change and not thinking clearly, they probably also lack the knowledge that the gorilla “presenting” the child is engaging in behavior meant to reinforce social status, i.e. behavior a large number of primate onlookers can potentially affect. Apart from a mild sense that crowding animals makes them tense – and how crowded they can get depends on design exhibit – it probably doesn’t even occur to most of the people in the crowd that they are capable of making the situation worse (or better).

Bad response by the Internet, animals aren’t people and bad bad bad … keeping animals in zoos is inherently wrong – The complexities inherent in these two views come down to “what is an animal?”. It’s one thing to say “I don’t eat meat”, which becomes complex when, for some people, fish and chicken aren’t included in the term “meat”. It’s quite another when you have people thinking that keeping animals in captivity is wrong but missing the fact that there is no natural habitat left and that without zoos, we’d have no place to put animals that get injured in the wild. It misses the ethical complexity of keeping cows and pigs in captivity while fighting against the captive situations in zoos. This attitude misses the complexities that life in the wild may be “free” but that animals in captivity often live longer lives with a lot fewer parasites and diseases than their wild counterparts … parasite and diseases that are becoming more prevalent as the overall health of the wild habitats degrades. It even misses the definition of what an “animal” is. If it’s not OK to eat animals or hold them captive, is it OK to kill a tapeworm that is living inside you? If you accept the “it’s OK to harm what’s harming me” ethical counter, is it OK to use antibiotics to save a life, even if they kill trillions of microorganisms? What about the mice and birds that live in a cornfield and are killed when the field is harvested? Where is the line?

—

The answer, of course, is that there are no lines. If you look at nature, you see categories blending into other categories. There is no firm line between forest and field just as where a river stops and an ocean begins is blurry. What we once thought of as a food chain is now a food web, which doesn’t break but does suffer from trophic cascades as problems occur. What we used to think of as an animal we are now starting to see as a complex interplay of a major genome with all the various microorganisms living within it.

When we are faced with an emergency, we tend to make decisions based on a highly simplified mental model of what’s actually going on. What we see as gorilla with a kid is actually the interplay of a very complex system involving a gorilla and a child, that child’s parents, the gorilla’s keepers, the keepers’ bosses, the parents’ associates forming the crowd, people on the Internet, citizens of Cincinnati, and the historical weight of previous decisions made at that zoo and various other zoos throughout time. But we don’t see that in the moment. We don’t see the ecology we live in. We just see the parts.

This is the same as when we are asked to accept a small tax raise to improve infrastructure. We don’t see the pattern of failing bridges. We see the one bridge we drive over every day and it always seems fine. We don’t continue to invest in a successful space or science program, contrarily, because it is successful. When the payoff is to keep things the same, we try to do it for less money. When the payoff is to keep bad things from happening, we look at the past and think “it never happened before” and use the money to buy what we want.

It’s when the payoff is unknown and uncertain that this works against us. If we won’t know the value of a thing until we invent it, we tend to just do without, allocating funding to things that are more certain instead of making small investments in discovery that could have extraordinary payoffs in the future. This is why we have so many stories about inventors creating something awesome in their basement … they didn’t have another option.

No, we only spend money when it’s an emergency. Due to this issue, the Cincinnati zoo is going to invest in infrastructure. Other zoos will use this event to get funds to do the same. Of course, it would have been a lot cheaper to implement these sorts of changes before the emergency happened. It’s always cheaper to invest in improving preschool than it is in reforming criminals that were failed by a poor educational system. It’s cheaper to invest in system hardening than it is to recover from a hack. It’s cheaper to get regular dental cleanings than it is to have teeth pulled.

But no, humans are story driven, and “we need to keep the good situation from changing” sounds an awful lot like “we need to make nothing happen, and it’s going to keep costing money”.

Emergencies, on the other hand, make for excellent stories.

Because it is Tuesday and time for my weekly pointer to Turtle Tracts (here: https://igg.me/at/turtletracts/x ), I just want to mention that the point of the project is to study the complexity of the oceans and of the sea turtles themselves. We are at a point in the science where, if the $10,000 two-year goal is met and the research is done, it could save millions of “fix it” money in the future … if it’s even fixable.

A zoo exhibit can be improved after an issue is discovered when a gorilla dies. No matter what we spend, though, we’ll never get that gorilla back.

Eventually, I have no doubt that we’ll be able to fix the oceans. I just hope there are still some turtles left when we do, because if there aren’t, we’ll never get them back.

Infrared bug

Infrared heron fight

Thinking About Gorillas – Part 1 – Thinking Tactically

Most of you reading this know me personally or through the animal/zoo/conservation world. I seldom talk about my day job here, because this is sort of a break from that. However, for most waking hours out of each day, I do business security work. I am, in fact, working on a few books on the overlap of the conservation and information security worlds, though they are quite a long way from being ready. However, with the recent news coming from Cincinnati, I have to make a few observations in this, part one of a two part post.

I will attempt to not re-hash what you already know about the incident, so if you don’t know what I’m talking about, here is a very quick summary:

- The Cincinnati Zoo’s gorilla enclosure opened in 1978. Until a few weeks ago, there had been no issues.

- On May 28th, 2016, a young child bypassed several barriers and wound up inside the gorilla enclosure.

- The child was discovered by a relatively young male gorilla, who started moving him around and using him in a status display.

- The keepers attempted to separate the child from the gorilla, but were unable to do so, though they did get other gorillas out of the way.

- Due to a lack of other options, the zoo decided that the young child’s life was in serious danger and that the only option was to kill the gorilla.

- Because we live in the age of out-of-context smartphone video, this was all recorded so …

- The Internet lost its collective shit and, over a single weekend, millions of people suddenly became self-proclaimed experts in wildlife management and tranquilizers.

Because people are always looking for ways to improve their own lives and the overall state of the world, it’s not surprising that there was so much armchair quarterbacking going on after the zoo incident. In general, the problems people are discussing seem to break down as follows:

Bad parenting – This position states that the mother was fundamentally at fault because she lost control of her child. I think it’s hard to make the argument that anyone is a bad parent from a single dramatic incident unless the parent actively harmed their child. Anyone can have a bad day. Everyone who has had a child or even been responsible for one for a short period of time knows what it’s like to get distracted for a second only to find that the kid vanished in that moment. It happens millions of times each day. This one case just happened to involve a gorilla. I am more inclined towards sympathy than blame here.

Bad exhibit design – The exhibit was designed 40 years ago and completed in 1978. Since then, there have been a few similar incidents in other zoos. In 1986 at the Durrell Wildlife Park, a young child fell into their gorilla enclosure (built in 1959) and in 1996 the same thing happened at the Tropic World (built in 1982) exhibit at Brookfield Zoo in Chicago. In those two incidents, the gorilla who discovered the child protected the child from the others. However, one of the discovering gorillas was the dominant male and didn’t need to gain status and the other was a mother who was already engaged in the normal behavior of protecting her own child from other gorillas.

Additionally, according to my zoo feeds, in the same week that the young child bypassed the barriers and got into the gorilla enclosure, two lions had to be killed when a suicidal adult jumped into the Santiago Metropolitan Zoo and two drunk men were bitten by bears when they broke into the Roosevelt Park Zoo. If you follow zoo news, you see that people bypassing barriers isn’t nearly as rare as you’d think. Most zoos build multiple barriers. In this case, there were fences, bushes, and a moat … as well as a big dangerous animal inside. Most humans recognize those as “stay away” signals.

I think it’s fair to say that after three such events in similarly-designed exhibits, there might be a flaw. However, any security system – in this case the specific system in place at the Cincinnati Zoo – that can run 40 years with only one incident has done most things right. A well designed exhibit allows people to appreciate the animals while also keeping the people and animals apart. There should be physical barriers, visual warnings, and systems designed to activate if the passive barriers fail. While I have some thoughts on how this could be improved, speaking as a security professional, I can say that no valid recommendations can be made without proper inspection and modeling and that immediate reflexive responses, as we saw after 9/11, are often both ineffective and consume resources that could be spent on better approaches.

Bad response by zookeepers – Many people have suggested that the zoo should have lured the gorilla off exhibit and/or used tranquilizers rather than just shooting him. These people clearly have little understanding of how tranquilizers work and how animals who have been tranquilized behave. Gorillas are primates and tranquilizers are drugs. Humans are also primates who have a lot of experience with drugs. Gorillas like fruit and so do humans. So here’s an experiment you can run to see how well such an approach would have worked.

On a Friday or Saturday evening, go to a bar where male humans put on displays to gain status and offer them a handful of blueberries in exchange for their status symbol, be it a car, fancy necklace, or smartphone. See how they respond. Then, as they consume alcohol (a depressant, like tranquilizers) see if they are more or less inclined to accept your offer. Now imagine that they are 800 pounds, ten times as strong as humans, and that the object is a small three year old child.

The truth is that zookeepers train for this. I was fortunate to observe one such training just last year. Every keeper is trained in both mixing and firing the darts. Darts must be mixed live because the tranquilizer mix must be dosed for the specific animal and doesn’t have a very long shelf life. Just keeping the drugs on hand and not used is a very significant expense, but one that all accredited zoos incur because they understand the importance of tranquilizers in a human/animal encounter. They know the weights of all their animals and practice mixing and firing the darts on a regular basis.

Sadly, all zoos also have shotguns and/or rifles and an emergency plan because tranquilizers aren’t perfect and animals don’t always do what they’re told. No one wants to kill an endangered animal that they, maybe personally, have raised for years, but they recognize the necessity. Like farmers, zookeepers live day-in and day-out with animals and they know that part of life is death. They are professionals and like other professionals who deal with life and death – police, surgeons, soldiers – we have the right to respectively question their actions in the aftermath. But is the height of arrogance to think that we would be able to make a better decision were we in their shoes.

Bad response by zoo visitors – Gorillas and humans are both primates. As humans crowded around the enclosure, the gorilla gained an audience and, with an audience and the child to use as a status object, the attention made his behavior worse. If you read the reports of primate experts weighing in on the issue, they all seem to be in agreement with this interpretation. The best thing for people to do to defuse the situation would have been to leave, so the keepers could work with the gorilla. This is, however, a very hard thing for people to do. When enough people get together, the crowd gains a mind of its own and it takes a very strong leader to take control over it.

All we can do here is to recognize that we behave this way and regret that no strong leader was there to get the people to all leave so the keepers could contain the situation.

Bad response by the Internet, animals aren’t people – There is a prevailing attitude among people that people are better than animals. It’s what keeps our species alive. We all have this to varying degrees. At the far end of the spectrum is that classic Western view of Genesis 1:28-31 where animals are specifically given to humanity to use as we see fit. As the other end is the Jain Dharma, in which all other living things should be harmed as little as possible. In the middle are various ways that humans can interact with animals, whether we eat them, pet them, ride them, love them, or hate them.

The relationship is a very complex one and, when analyzed, most people seem to land somewhere between “I see nothing wrong with eating all the animals I’ve grown up eating but leave my pet alone” and “I am trying to minimize meat in my diet and I love my cat”, with a few at either end claiming pride as carnivores or vegans.

However, the reality is that all ethics aside, politically the zoo had no choice but to kill the gorilla. Even if the belief system of an individual places a gorilla above a human in some subjective scale, the ramifications to the zoo as an institution and to the zookeepers as individuals are so much higher were they to make a decision that killed a kid that when it comes down to gorilla vs. human, human has to win every time. Success lies in crafting the environment such that that decision just doesn’t have to be made.

Bad bad bad … keeping animals in zoos is inherently wrong – As happens every time, the anti-captivity movement jumped all over this incident in an attempt to push their agenda. Various articles and opinion pieces have been published that claim that all captivity is wrong and that this is yet another example of why all zoos should be closed. In some ways, this is much along the same line as the vegan belief that humans should not eat animals, and that we must respect them. As someone who is very sympathetic to this view and lays much closer to the “animals and humans are the same” side of the spectrum, I am still baffled that this movement even exists.

Yes, life for an animal in even the best zoo is not going to be as pleasant as the idealized life in the forest, field, or sea. However, we don’t have idealized forests, fields, or seas. We have forests that have been stripped of all trees and re-planted as monocultures that can support maybe a tenth of the animals they once did. We have fields that have been turned into parking lots, cities, and cropland. We have seas that are becoming so full of plastic that whales are starving to death with full stomachs. How can anyone can legitimately say that zoos should be closed down and all the animals let free into habitats that no longer exist and not be actively involved in preserving or recreating those habitats?

It’s easier to criticize than it is to fix things.

Tomorrow I will review the same issue from a strategic direction.

Shifts

Sometimes infrared makes things look extremely different. When I am shooting my new camera, everything looks weird. Due to the oddities of how digital IR works, all the reds and blues are “flipped” from what you (usually) want. This results in bright red skies which can be very distracting. However, you can still see the differences. In this photo, for example, I could tell right away that there was something interesting about those seed pods because, outside of the camera, they are the exact same brown as the ground and the leaf.

Sometimes I just hold the camera up to my eye and walk around, just so I can see things differently.

Bug

Caterpillar

Damelfly

So why am I doing this? Well, one reason is that some animals are bothered by flash. This photo was taken with an infrared flashlight in one hand and the camera in the other. It’s not easy (and surprisingly tiring), but when it works, the camera can lock on and you get a photo like this in a way that the animal never sees any additional light.

This isn’t such a big deal for insects like this, but it matters a lot for nesting reptiles and birds as well as foraging mammals.

Wood Lake

Infrared Wood Lake – Hotspot 2

Infrared Wood Lake – False Colour

So I finally took the leap and converted my backup camera to infrared. Unlike my previous infrared camera, this one records a much larger range of wavelengths so it’s faster and allows me to a “false” colour view. The problem, however, is that some lenses apparently have a “hot spot” in which the center of the sensor collects more infrared light than the rest so you get colour shifting.

It works out OK when you can line it up with a lens flare.

Red Fox

Zoo glass is well-designed for it’s primary purpose. It can keep big dangerous animals on one side and still allow big humans to gawk at them from the other side. It’ll scratch, but it’s not terrible. There’s a slight greenish cast to it, but most people don’t notice and photographers can easily correct for it (if they have full colour vision … those lucky bastards).

One problem with it, though, is that it’ll etch over time and get a bit cloudy. Also, since it’s rather thick, it’s harder to shoot at an angle without it really changing things on the sides of the image.

Sometimes, however, that works out OK.

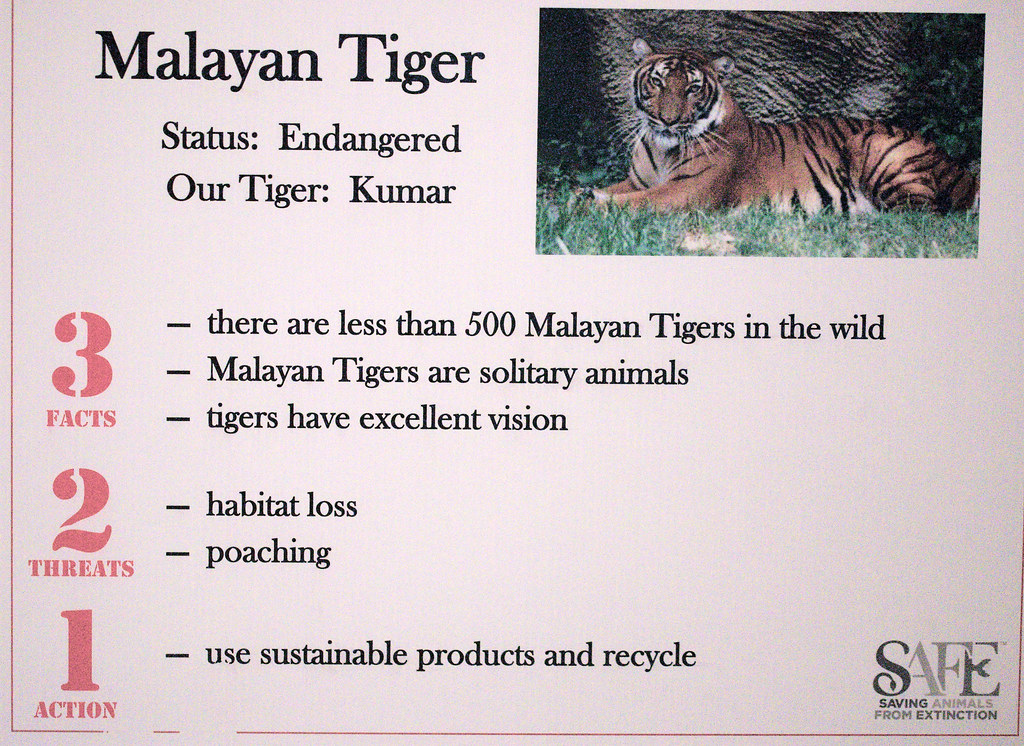

Sign

I am not an expert in sign design, but I think this system used at the Birmingham Zoo is fantastic. Yes, the reality of an ecosystem is far more complex than a 3-2-1 approach allows, but since the average person in the US has been lied to all their lives and forced away from science education, it’s one of the most effective systems I’ve seen for reaching the masses.

African Wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica)

Surprisingly, with all the zoos I’ve visited, this is the first African Wildcat I’ve seen. This is an interesting side effect of zoos working to save critically endangered species. The wildcat is rated “Least Concern”, so no one is working to actively breed it. I don’t know if this specific animal as a rescue, but if you want to see exotic non-rare species, rescue centers or zoos that work with law enforcement (working against the illegal pet trade) is the way to do it.

When you travel to different zoos, you really start to see many of the same species … those that are endangered but that can also probably be bred. The critically endangered animals that *might* be able to be bred are usually in breeding centers away from the public. Sadly, the critically endangered animals that cannot be bred, for whatever reason, are largely left to their own devices within a rapidly shrinking and worsening habitat.

So many of the animals I see are endangered, some are critically endangered, but the most critically endangered animals on the planet are ones that I will likely never be able to see. Still, I’m glad to see what I have been able to see.

Squirrel

With a very expensive tilt lens, I could have gotten the squirrel in perfect focus without having that distracting line of focus going down the slope. (Cost: $2,000)

Another approach would be to use a LensBaby Lens Composer, which isn’t as good as a tilt lens, but a lot cheaper (Cost: $300)

Alternatively, I could achieve a similar effect with a tilt/shift adapter or a bellows unit for an existing lens. (Cost: $100 – 200)

Yet another way to do it would be to use Photoshop and just blur that area out. (Cost: $30/mo)

However, there are free and “cloud” options like Photoshop Express, GIMP, and Pixlr. (Cost: $0 + the time to learn something new)

The option I chose, of course, is do nothing and spend the time I could have spent correcting the issue researching the costs of how to fix the problem, ’cause I’m all meta and stuff.