As noted earlier, birds are dinosaurs. Back when they were dinosaurs, it was much harder to get shots like this because of the size issue. The larger a creature is, the more light you need to freeze the action. This shot was possible with a small bird using only two small flash units. Doing this with a large dinosaur would have required at least ten flash units, an assembly of light trees to position them properly, a very large piece of fruit and the invention of photography.

Grey Crowned Crane (Balearica regulorum)

It’s hard to get a good bird portrait. Ideally, such a shot is against a very smooth background and is composed such that the iris is in crystal-sharp focus and there’s a bit of light on the eye. These “catchlights” look very different on living animals than on stuffed or dead ones and helps to psychologically convince the viewer that the animal is healthy. Birds are particularly difficult because they’re constantly preening their feathers, so are in constant movement. Thus, as they move their head, the background changes, the focus changes and many positions cause the catchlight in the eye to go away. Getting a good shot largely involves a mix of luck and patience. Good lenses help, but really, patience overwhelms every other consideration.

Collared Mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus)

Wolf Cub

Nicobar Pigeon

Prairie Dog performing Macbeth

Black Footed Cat

Black-footed cats are the smallest breed of wild cats, seldom exceeding three pounds in weight. Despite this being extremely clear on the sign, grown adults will coo over it and call it a baby. I must conclude that this is because they’re so cute that their mere presence temporarily overrides a human’s ability to read. Because the alternative, that zoos attract a stunningly large number of babbling idiots on Saturdays, is too horrible to contemplate.

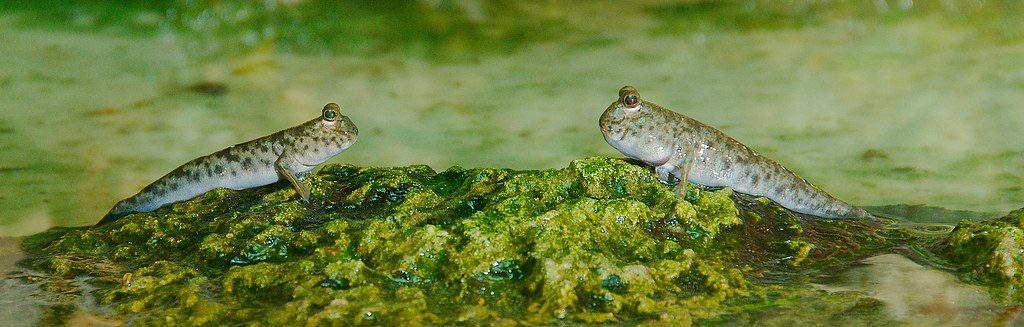

Mudskipper

Nene (Branta sandvicensis)

Eastern Lubber Grasshopper (Romalea microptera)

Florida Orb Web Spider (Nephila clavipes)

It started as a thrum, soft, almost unnoticeable. Some felt it as a slight sense of unease. Some, a dull worry. At first it was the sensitive ones, the artists mostly. They spoke of the changing times, wrote music, painted, sculpted. It was an age of widespread creativity. Then it was the protectors, who worked with the artists to create edifices of magnificent beauty and function.

But it wasn’t enough.

The thrum became an itch. A slight tingle in the center of the brain, more insistent year by year. More noticed. Artists became activists. Defenders became fighters. War raged — without regard for country or creed. Those in power needed battle. Those oppressed needed to fight. Only action could scratch the itch, could make it tolerable. If one couldn’t fight in person, one could fight by proxy … watching or controlling avatars on screens.

But it still wasn’t enough.

No longer an itch, it became a steady vibration interspersed with a beat. Everyone noticed it now. They felt driven. They feared. They panicked. They began to accumulate wealth. Those with the most needed the most. Those without defended themselves through community. They drew together, into conclaves of outrage. Lines were drawn, crossed, and drawn again. War raged again, but more personally, more viscously.

But the vibration continued, the beat grew ever stronger.

One day, a city vanished, crumbling into rubble overnight. That’s when they realized it wasn’t all in their minds. Sensitive instruments were developed. Detection and triangulation pointed towards a source. More machines were built. Machines that could see further than before, deeper than before. Five more cities crumbled before they succeeded, when the universe began to become clear.

They saw their world, a mere dot, connected to many many others. They began to understand the vast distances they knew of and the newly discovered, thin tendrils linking them together. They developed new technologies to talk to nearby worlds. Those nearer the source had nothing to offer but broadcasts of immense devastation. Looking further, there was nothing but planets in shards, glistening among the blue. The looked away from the source and detected pristine worlds, though some with evidence of growing war.

Still, cities crumbled, islands sank, volcanoes erupted and then melted into oblivion.

They improved their technologies. And, in seeking at greater and greater distances detected nothing but dead and dying worlds in one direction and oblivious and silent ones in the other. They tried to seek even further and saw nothing but mist in the deep distance and, occasionally, movement.

Then their moon exploded, scattering splinters across the cosmos.

They felt utterly alone.

But they weren’t.

Pygmy Marmoset (Cebuella pygmaea)

Kettle of Hawks

Throwback Thursday

This fish might be a goby. It might be something else. It might be defending its burrow, it might be advertising for a mate. If it is advertising for a mate, it might decide to be either male or female, or it might decide to sneak into someone else’s mating session and provide a contribution. Frankly, there is too much uncertainty involving this fish and it should be thrown back. (Though if it’s a frillfin goby, it might jump back, so check for that first.)

Malagasy giant chameleon (Furcifer oustaleti)

The Malagasy giant chameleon is a good start for a beginner lizard climber, but provides a lot of fun for advanced climbers as well. The nose approach is the most common, but some prefer the challenge of the lower lip followed by a rope looped over the eye socket. This is particular challenging during fruit fly season when the eye moves around seemingly at random.

Galapagos Tortoise

Black-and-white Ruffed Lemur (Varecia variegata)

Rainbow Lorikeet (Trichoglossus haematodus)

Snake

On Porcupines

Porcupines are pointy.

Well, not when we’re babies. Or if we have mange.

Or, I suppose, if we shave off our quills, but only the weird porcupines do that.

Anyway, the point here is if you meet a porcupine, odds are, that porcupine is going to be pointy.

In fact, if you get to know a porcupine, there’s a chance you may get poked.

That kinda goes hand in hand (or paw in paw) with the whole porcupiney lifestyle.

We don’t mean to do it. We’re normally careful.

Sometimes though, it just happens. Usually because we don’t communicate well beforehand.

Well sorta.

I don’t like to admit it, but some porcupines are assholes.

They poke you on purpose.

They think it’s fun.

When we talk about porcupines, we don’t really think of those porcupines.

When we were growing up, we avoided those porcupines. They were mean.

Still, the rule growing up was, “all porcupines gotta be put together”,

so there they were, hanging out in the locker room, being all pointy and stuff.

You had to watch out too, ’cause as soon as you weren’t watching, you’d get poked and they’d all laugh.

Not only that, but you had to laugh when your friends got poked, because otherwise, next time, they’d poke you.

We avoided them then as much as we could, and now that we’re all grown up, we still do.

I mean, who would hang around with assholes on purpose.

The thing is, they’re still around. I can recognize them, ’cause I’ve met a lot of them over the years.

When I meet one as an adult, I just mentally think “pointy asshole” and find somewhere else to go.

Sad to say, I’m still a bit afraid of getting poked.

Anyway, the “point”, of all of this is that you’re probably not a porcupine.

Not being a porcupine, you probably can’t tell the regular occasionally, accidentally, pokey porcupines from the asshole pokey porcupines.

I’m know you know that #NotAllPorcupines are pokey assholes. But I also know that some are …

… and not being a porcupine, it’s probably hard for you to know ahead of time which ones are the assholes.

So you’ll be wary.

Probably because you’ve either know someone who has been poked, or have been poked yourself.

I’m sorry.

That sucks.