Lemur suddenly realizing that life is a series of unlikely events, each effected by that which preceded it, and that there is no way to know if one has free will or if one is merely responding to billions of years of physical, chemical, and biological dependencies.

Indian Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis)

Southern Bald Ibis (Geronticus calvus)

Again, from Wikipedia:

Vocalizations

The Southern Bald Ibis is known to be a relatively quiet bird. This species in particular has been noted to make a weak gobbling sound. This is refers back to their old Afrikaans name of “Wilde-Kalkoen”, otherwise translated as “wild turkey”. This bird is most boisterous in the nesting areas and in flight. It projects a high-pitched keeaaw-klaup-klaup call, resembling that of a turkey’s.

OK. It gobbles, so it’s like a turkey. Except, it’s like a turkey that makes a high-pitched “keeaaw-klaup-klaup”, which I’ve never heard a turkey do. That aside though, think about this …

The bird’s name in Afrikaans translates as “wild turkey”. This means that the following must have happened.

* Sometime in ancient history: Europeans go to Turkey and see a guinea fowl, which was actually imported from Africa.

* Sometime in the 1500’s: Europeans go to North America and see a bird that they believe to be related to the guinea fowl (it’s not) and name it after Turkey, the country.

* Sometime in the 1600’s: Europeans go to Southern Africa and, frankly, don’t treat the natives very well.

* Sometime in the 1700’s: Europeans in Southern Africa start making people speak Dutch, but it doesn’t take, and Afrikaans starts to form.

* Sometime in the 1800’s: Afrikaans replaces Malay as a primary language (due to forced schooling) and the old words get lost.

* Sometime after that: Someone points to a bird and says “What’s that?” in Afrikaans. Since it doesn’t have a name in Afrikaans yet, someone who knows what an American Turkey is hears its noise and names it after a North American bird, which is named after a Turkish bird, which is actually an African bird that is entirely different from this particular African bird.

* Sometime after that: It gets written down that way and we’re stuck with it forever.

The Europeans have some things to answer for, is what I’m trying to say here.

Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus)

This is a vulture. This is obviously a vulture to anyone who has ever seen a vulture anywhere.

Nonetheless, this bird is also known as a “gier-eagle” (derived from the Hebrew root for “to love”, reflecting that the birds live in mated pairs.) It is listed as an unclean animal in Deuteronomy 14:17 and Leviticus 11:13.

Yet, for some reason, it is also known as a “Pharaoh’s chicken”, though the Internet is rather less enlightening as to why except that it might be the fault of Henry Hunter (1741–1802) of the Church of Scotland.

Gaur (Bos gaurus)

Wrinkled Hornbill (Aceros corrugatus)

Gerenuk (Litocranius walleri)

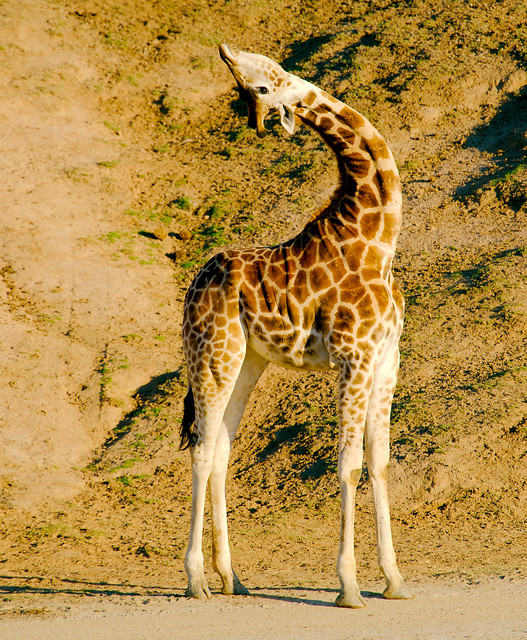

Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis)

Park

White-crowned Plover (Vanellus albiceps)

I was confused for a while because these plovers looked a lot like the lapwings I’d seen … so I looked it up.

You’ve got your Charadriiformes, which are a bunch of birds that are mostly watery. The sub-order Charadrii are entirely watery, being wading birds. All plovers, lapwings and dotterels are in the family Charadriidae. Lapwings, in particular, are in the sub-family Vanellinae, which are distinguished from the others in Charadriidae as having crests. While all the lapwings are Vanellinae, not all Vanellinae are lapwings because in addition to lapwings, the group Vanellinae includes the red-kneed dotterel.

So it basically works like this:

Kingdom: Animalia (We’ve got cells and can move and eat things.)

Phylum: Chordata (… and a spine)

Class: Aves (… and feathers)

Subclass: Neornithes (… and we’re currently alive)

Infraclass: Neognathae (… and modern jaws.)

Superorder: Neoaves (But we’re not ducks or chickens.)

Order: Charadriiformes (We like water.)

Suborder: Charadrii (We *really* like water.)

Family: Charadriidae (We have short, thick necks. Our wings are usually pointed but sometimes not. Our bills are usually straight, but sometimes not. We usually have short tails, but sometimes not. Our hind toe may or may not exist. OK, it’s a bit of a mess.)

Subfamily: Vanellinae (We have crests.)

Common Name: Lapwing (We fly funny.)

Come and see the confusion inherent in the system.

Addax (Addax nasomaculatus)

Ring-tailed Lemur (Lemur catta)

Addax (Addax nasomaculatus)

In the wild, animals that destroy their environments tend to be nomads. Hooved animals like these will move as a herd so the land can recover. Elephants move through the forests knocking over trees, but it takes long enough that more trees grow back.

Humans just run out of space and then start being meaner to one another.

Southern Square-lipped Rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum)

African Openbill Stork (Anastomus lamelligerus)

San Clemente Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus mearnsi)

In honor of Independence Day, here is an all American bird.

The San Clemente Loggerhead Shrike lives on an island used by the US Navy for target practice. Due to the importation of goats (and, presumably, bombs), their population dropped down to 14 birds. Today, there are nearly 200. This is due to a combination of the Navy improving the use of their land, such as removing goats (but not, presumably, bombs) and captive breeding.

The graph below is particularly interesting because it shows the value of captive breeding and reintroduction programs. These programs, of course, take a while to take effect as animals must reach sexual maturity, but when they get there, wow.

(Facebook people should click here to see the graph: http://www.iws.org/species_loggerhead_shrike.html )

Addax

In addition to their bird breeding, the San Diego Safari Park breeds mammals. Anecdotally, it appears as though we have an easier time breeding hooved mammals than other types of mammals. There are, for example, less than 500 wild addaxes (addaxen?) but over three times as many being bred in captivity.

This means that sights like this one may be on the rise.

Congo Peafowl (Afropavo congensis)

Gerenuk (Litocranius walleri)

San Diego Safari Park

In December of 2015, I returned once again to the San Diego Safari Park (formerly known as the San Diego Wild Animal Park). When I set up the trip, I had planned to re-visit Nola (first visit described here: http://stories.starmind.org/northern-white-rhinoceros-ceratotherium-cottoni/ ), but that turned out not to be possible. Since the trip was already booked, we pivoted to focus on the Bird Breeding Center (aka the BBC, but not that BBC.)

Upcoming photos will focus on rare birds as well as the normal sorts of photography I do. The difference with the birds is that, unlike a zoo where birds are on display, a breeding center is more focused on creating privacy for the birds (so they’ll mate). This means that angles and lighting are even harder to get right than in a traditional zoo setting.

So, to make up for the upcoming lack in quality, here is a photo of a worker driving a safari truck into the little rivulet.

This shot was taken from half a mile away.