This week for TTT, I want to think about sleep.

Recent studies exploring sleep have been interesting to pursue. Back when I was first learning about science, I was told that fish didn’t sleep, that birds didn’t sleep when migrating over the ocean, and that trees didn’t sleep. As it turns out, all of these are false. Fish sink and rest on the bottom to recover their energy (sometimes digging into sand, sometimes cocooning themselves in mucus. Birds can sleep in the air, sometimes not landing for hundreds of days. And, most recently, we learned that trees droop into a form of “sleep” at night. That’s scientific discovery for you.

A decade ago, perhaps, you lived in a world where you planted a tree in the backyard to shade the house. Now, you live in a world where a sleeping giant towers over your bedroom, providing homes to different dreamers … snoozing squirrels in the branches, dormant deer around the trunk and, in their roots, torpid tortoises.

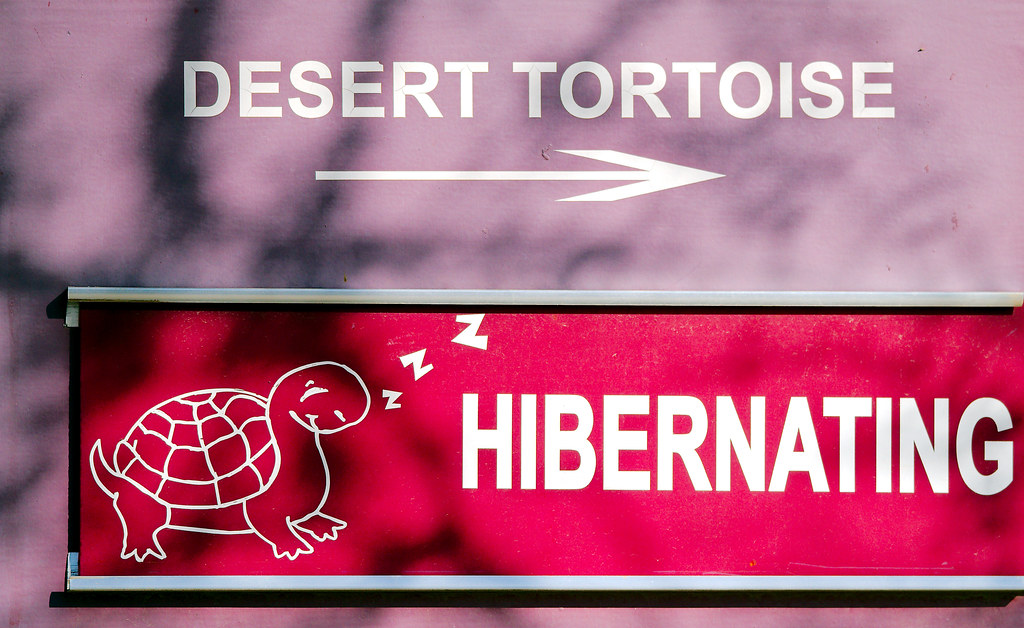

Terrapins, turtles, and tortoises (don’t bother looking up the difference, it’s a maze of twisty little passages, all alike) all sleep normally, but also have a form of long-term sleep. Sometimes it’s called hibernation, sometimes æstivation and they do it to avoid environmental extremes. When it’s too hot or too cold, they suspend their metabolism and find a safe place to wait it out. It’s a finely tuned process that has worked well for millennia … when things go as planned.

As scientists have learned with both frogs and turtles, if their natural cycles are interrupted, things can go badly wrong. The mountain yellow-legged frog hibernates each winter and, if they don’t get their 40,000 winks, they don’t breed in the spring. As this is an endangered species, it was rather important for people to figure out why the breeding program wasn’t working well before their rescue population of frogs aged out. A similar issue happened with the western swamp turtle, where weekly health checks woke the turtles from their summer æstivation, preventing them from being healthy enough to reproduce.

There’s a lot of weirdness in nature. For turtles in particular:

- A turtle’s shell is a modified spine and rib combination. Neil Shubin’s work on embryonic development, excellently written up in Your Inner Fish, recently shed some light on how this happens, with specific genes triggering the development of specific aspects of the skeletal structure, the same code being used throughout all animals.

- Like the rest of us, turtles need oxygen to survive. They all breathe air through their mouth, but some of them can engage in cloacal or buccopharyngeal breathing, where they bring in water or air through their mouthes or cloaca (the so-called “bum breathing”). This allows them to survive in oxygenated water when they cannot safely surface.

- Male and female turtles often look very similar to one another, even having similar genitalia. They identify their respective sexes through pheromones, a type of hormone that has been around for billions of years but that humanity discovered less than a century ago. It wasn’t until 1992 that we even gained the ability to measure pheromones outside of a lab.

- Speaking of sex, the sex of the turtle that hatches is dependent on the temperature of the egg in the nest. If it’s too cold, they all hatch as males. If it’s too warm, as females. To get a stable population, the eggs need to be around 50/50.

But what does this all mean in a warming world? Is it possible that higher temperatures will shift the sex ratios of the eggs, resulting in an imbalance? With an ocean of rising acidity and more calcium bonded to carbon, will their have difficulty forming shells from their ribs and spines, leaving them less well protected against predators? In a world where oceans and lakes can store less oxygen, will turtles’ breathing methods fail them, requiring them to spend more time surfacing and less time eating or evading predators? Will a warmer climate cause their pheromones to break down quicker, making it harder to find mates? Is it possible that warmer temperatures will reduce hibernation time and increase æstivation time, so turtles spend too much or too little of their time asleep and their pheromone release is hampered, so they don’t mate?

The answer to all of these is “maybe”.

The fact is that there’s a lot we don’t know and it’s a race to find out before a species is gone. It’s never as simple as “Save the Turtles”. Ecology is a big tangled mess (even worse than the tangled terrapin/turtle/tortoise taxonomy tumult), and isolating the important bits from complex ecologies is hard work. It was hard work to identify how skeletons form. It was hard work to figure out how to track invisible, scentless pheremones. It was surprisingly easy to figure out how turtles were breathing (they just dropped food colouring in the water) … but most of it requires someone with an idea and a bit of funding.

CuraEarth has the idea: untangle the ecology living on and inside of turtles to track how they’re doing and learn other interesting things along the way. They just need the funding: https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/turtletracts-studying-microbiomes-for-sea-turtles/#/

If you could spare even $5, it would help a lot to raise the profile of the project.