A few days ago, someone broke into a zoo and was bitten by a tiger. This happens and, based on my discussions with zookeepers, is one of the fundamental design criteria when creating an exhibit. Yes, it is important to create a place in which the animal can be as intellectually and emotionally fulfilled as possible, and that it be kept healthy and kept from getting out. However, it’s just as important to keep people from getting in. If you follow zoo news, you’d notice that there about as many stories about stupid people breaking into cages as there are about clever animals breaking out.

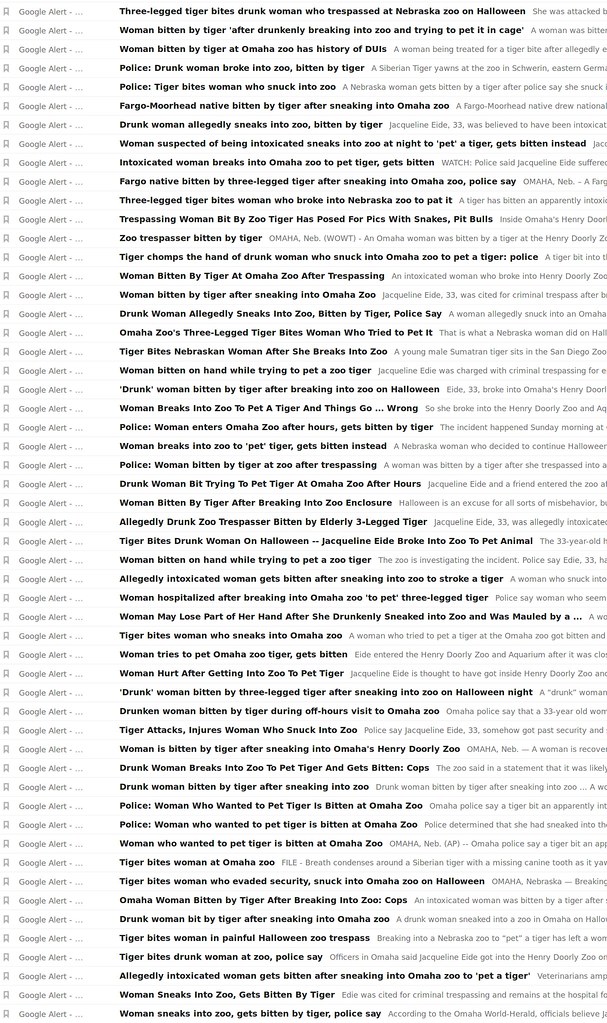

Below, however, is a list of headlines for this one single incident. This comes from a Google Alert on the word “zoo” because I find it’s a good way to get an unfiltered view of what’s happening. This one, however, is fascinating because of the way the headlines came out. Take a look at the headlines below, then, if you have time, take the time to read McSweeny’s “Interactive Guide to Ambiguous Grammar,” that explores this issue deeper more deeply than I will be able to.

Basic statistics

This is a list of 56 different headlines for the exact same incident. Let’s take a look at what the authors thought were the most important pieces of information for us to know:

- All of the articles mention a tiger. That makes sense. After all, that is the news story here. If someone breaks into the zoo, but behaves perfectly politely while inside, it likely would not have received nearly as much media attention.

- 50 articles, 89.2%, think that the person’s sex is important information. Sure, the English language would use “man” in this context should things be reversed, but still, I have my doubts as to whether or not sex and gender are a critical factor in tiger bites.

- 20 articles, or 35.7% of them, feel that it’s very important that you know the person was drunk or allegedly drunk. Early articles mentioned that she was high, but subsequent ones suggest that her reactions were due to shock. As that phrasing doesn’t appear in these headlines, I am ignoring it.

- Speaking of “allegedly”, a mere six articles, just over ten percent, mention that it’s still rather recent information and all the facts aren’t in yet. Two of them say that there may or may not have been trespassing. Four of them say that there may or may not have been drinking involved. None of them give the tiger an out though. Everyone seems certain that the bite came from a tiger.

- Some of them, 12.5%, think that it’s important you know that the bite came from a three-legged tiger. I’m not sure if that implies that it’s somehow worse to get bitten by a disabled animal, or if they’re going for the irony angle of an animal with three appendages damaging someone’s fourth.

- One headline – only one – mentions the person’s name.

Culpability of Entrance

However, digging a bit deeper, let’s take a look at culpability and blame. The facts are that it was after hours, the zoo was closed, and the area in which the tiger was located was off limits both during the day and at night. In order to get bitten, the person must have:

- Cross the external zoo barrier, be it over a fence or forcing a door (that’s how zoos work)

- Cross an internal zoo barrier to gain access to the tiger (that’s how zoo exhibits work)

- Cross a personal barrier, as otherwise the tiger wouldn’t have chosen to bite (that’s how cats work)

- Cross a time barrier, by entering the zoo after hours (that’s how opening hours work)

After all, if you were relaxing at home after a difficult day, and someone came into your yard, broke into your house, and tried to pet you, you’d probably bite them too.

Interestingly, of all the articles in this feed, only five describe the event as using anything other than “bite” or “bitten”. We get “hurt”, “injures”, the pretty intense choices of “mauls” and “chomps”, and my personal favorite “things go … wrong” (that’s midwestern understatement right there).

So we’re pretty sure we know what happened, but who was at fault in the view of the uninformed Internet writers who weren’t there? (Of which I am one, of course.)

If we view breaking or sneaking into a place or trespassing as a wrongful act, a whopping 69.6% of people seem to think the person was at fault. But really, it’s more of a spectrum. If we view breaking in to a place as worse than trespass, which is worse than evading security or sneaking around, you get the following breakdown:

- “Broke in” – 14

- “Trespassed” – 7

- “Snuck in” / “entered after hours” / “evaded security” – 24

- No blame assigned to the person’s entrance – 5

(There were also six headlines that were unrelated to the entrance part of the story.)

What’s interesting here is how many writers seem to feel that the person was at fault in some way, but that entering a zoo after hours isn’t as bad as, say, breaking into a bank or house. “Sneaking” being less bad than “trespassing”, and “evading security” being less than “breaking in”, at least so far as most people use the words. Personally, since it’s a lot easier to replace stuff than it is to replace an endangered species, I don’t agree, but I seem to be in a minority here. (But at 25%, not a super tiny one.)

Culpability of the Bite

The other interesting way to view this list is to look at the act of the bite itself. Did the tiger bite the person or was the person bitten by the tiger? In the former case, the tiger has the agency to act and is an active participant in the incident. In the latter, the only actor in the story is the person, so they are completely to blame for what befalls them.

With this view comes a higher sense of blame than if you view the situation as one in which the person made a mistake and something bad happened to them as a result, such as if they chose to wander too close to a ledge and fell off. No one thinks the ledge is at fault in such a situation, so the say “the person fell off the ledge”, not “the ledge threw the person”. If, however, the person is walking at a safe distance and there was a problem with the ledge, we would say “the ledge gave way”.

So if we review the list once again, looking at the bites, we learn that the active voice was used 13 times, whereas in 39 times the headline writers used passive voice. Thus, three times as many people chose to attribute the bite to the person than to the tiger based on very limited data.

The Stories We Tell Ourselves

None of these findings should be a surprise. They do, after all, match the story we want to tell. We like scary animal stories, but we also like stories about underdogs and stupid people. Specifically mentioning the fact that the tiger only had three legs and was old, casts the tiger as the underdog. Specifically mentioning that the person was drunk and female (unfairly) connect to many societal narratives about stupid people getting their comeuppance. So here, we have the scary incident in which a tiger bit someone, but we get to wrap inside a narrative where a female person who was probably drunk broke the rules and paid for it.

Consider the two most opposed headlines:

- Allegedly Drunk Zoo Trespasser Bitten by Elderly 3-Legged Tiger

- Tiger bites woman at Omaha zoo

In one story, we have a bumbling person violating law and normal expectations of society, tormenting an old, infirm, animal, and getting their just rewards. Extending this story from the other headlines of this type, we have a stupid woman screwing up and getting punished. This, sadly, is a story that we, as a society, love to tell.

In the other story, we have a vicious animal that attacks a poor, defenseless, woman. Again, this is a story that we, as a society, love to tell.

Implied Roles of Humans, Animals, and Zoos

So what does all of this mean? Is it just an interesting linguistic exercise?

I have to think no.

We are, at this time in history, faced with a fundamental question around the issue of animal rights. On one side, we have a group of people who believe that animals have no rights at all, that humans are intrinsically better than everything else, and by right of might or innate superiority, that we should be able to do whatever we want.

On the other side, we have people who believe that animals have rights, though the nature of those rights is under pretty fierce debate. There is the right to live which everyone (except, oddly, some extremist animal rights groups) seems to agree to. However, whether animals have a right to not be held captive is in direct opposition to their right to have a place to live in the wild. It doesn’t make much sense, but a lot of the animal rights fights around zoos are happening around this very basic issue.

While this is often stated as people being pro-zoo and anti-zoo, the discussion that is actually happening is really this:

- One side says that animals shouldn’t live in zoos.

- The other says that animals shouldn’t have to live in zoos.

It’s a discussion, at the core, about conservation of land and ecologies. That is not, however, the story we want to tell. We want to tell a story about stupid animal rights activists (often described as weak-hearted women) going up against the hunting / food / testing / zoo establishments (often personified as the manly men that have sometimes headed them), and getting what they deserve.

We want to tell a story about young, determined people (again, often described as women) going up against the cruel, vicious, zoo world, and we want to feel bad when they can’t free the polar bear or elephant from their painful captivity.

Personal Views

Personally, I do not blame the tiger for responding to what was likely interpreted as an attack. Whether the tiger had three legs or was elderly is irrelevant. An animal in captivity grows accustomed to their environment in the same way an animal in the wild does. Even in captivity, there are times when people are around and times when they are not.

In almost all of the cases I’ve read where an animal attacks in a zoo, it is because their environment changed in a way they didn’t anticipate. This the same whether a surprise human appears and steps into their personal space or a fleet of bulldozers appears and removes the forest behind their fleeing feet.

Also, I believe the woman made a mistake. Looking at some of the articles about this situation, she has a history of making mistakes. While it was probably inevitable that she would eventually get seriously injured or killed if she continued that pattern of behavior, I have a hard time thinking that anyone deserves to get their hand gnawed upon by a tiger. I empathize because, like her, I think tigers are pretty neat.

At a larger scale, I find it interesting how different people chose to report this incident. I wonder how different things would be if the person who was bitten was male, if the incident had happened at a less well-respected zoo, if it had been another type of animal than a tiger. I look at the biases inherent in the language used in the headlines alone and suspect it shows multiple divides within our society.

I see these same divides actively harming animals that the animal rights group claim to want to help. I wonder if there is any way to get the more action-oriented groups to spur on the more careful groups, as the situation is pretty dire for many species. At the same time, I hope that those groups who understand the complexities inherent in conservation can do something to soften those groups often referred to as “radical”. I wonder if their energy can be guided in directions that will help to create the environments in which we all want these animals to live, rather than just focusing on the easier task of destroying the environments that are not ideal.

Just as in language, order matters in conservation. The difference is, with language, we can sit down and talk to work things out. If we do things in the wrong order when lives are on the line, there may be none left when we finally get things right.